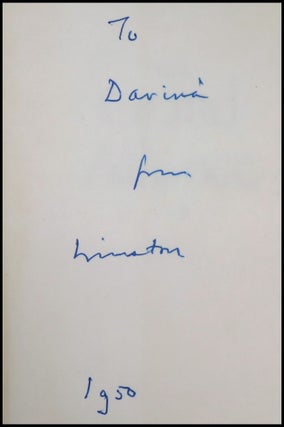

The Grand Alliance, the U.S. first edition of the third volume of Churchill’s history of the Second World War, inscribed and dated in the year of publication to Lady Davina Woodhouse - the daughter of Churchill’s first great love, widow of one Second World War hero, wife to another, and former mistress to Churchill's foreign secretary

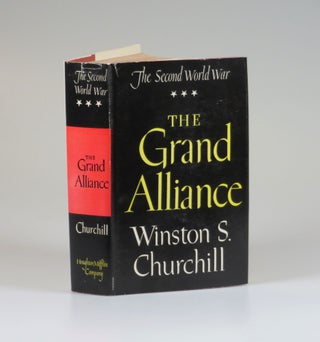

Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1950. First edition, first printing. Hardcover. This inscribed U.S. first edition of The Grand Alliance, the third volume of Winston S. Churchill’s Second World War memoirs, represents a compelling convergence of lives. First, the recipient - Lady Davina Woodhouse, the daughter of Churchill’s first great love, Pamela Plowden. Second, Davina’s husband, Monty Woodhouse, who inhabits some of the history recounted in this book, and who would likewise prove integral to geopolitical events during Churchill’s second and final premiership. Third is the man Davina did not marry, Anthony Eden, Churchill’s long-time lieutenant and long-delayed, ill-fated successor as Prime Minister.

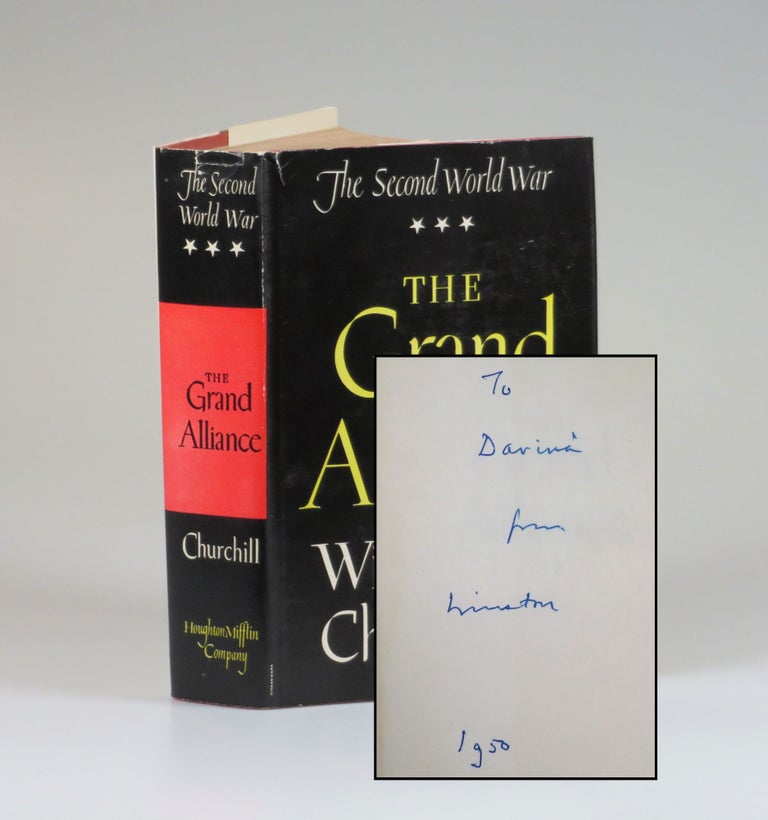

The inscription, five lines inked in blue on the front free endpaper recto, reads “To | Davina | from | Winston | 1950”.

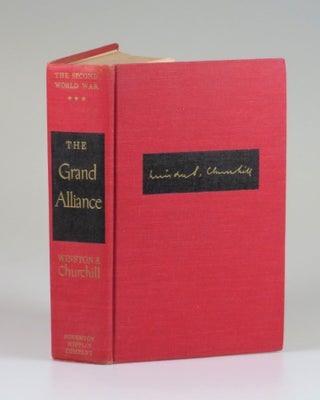

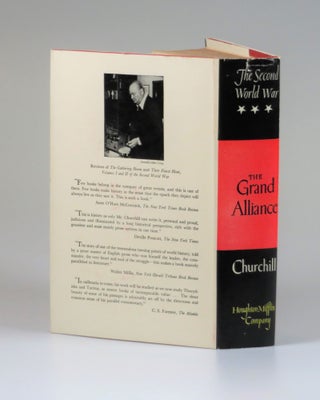

Condition of this inscribed copy approaches very good minus in a very good plus dust jacket. The red cloth binding remains bright and clean with minor shelf wear confined to extremities. The contents are respectably bright and clean. We find no previous ownership marks other than the author’s presentation inscription. The front hinge is slightly tender, but nonetheless solidly intact with no threat to binding integrity. The pastedowns are mildly browned from the glue. Light spotting is confined to the page edges. The original topstain is faded and the head and tail bands dimpled. Head and tail bands, dated title page, copyright page, topstain, and binding are all consonant with first printing of the first edition, as is the unclipped, “$6.00” price on the dust jacket flap. The jacket is bright, clean, and complete. Light wear is primarily confined to the spine head and adjacent upper front face, front hinge, and front flap fold. The red spine panel is only lightly sunned. The jacket is protected beneath a clear, removable, archival cover.

Lady Davidema “Davina” Katharine Cynthia Mary Millicent Bulwer-Lytton (1909-1995) was the daughter of Pamela Frances Audrey Bulwer-Lytton (née Plowden), Countess of Lytton (1874-1971). Winston Churchill met Pamela Plowden in India in late 1896. Pamela was Winston’s “first great love”. For several years, during his early career as an itinerant, adventure-seeking cavalry officer and war correspondent, “Churchill was obviously in love with this beautiful girl” and they maintained a robust and romantic correspondence. But in the end there was no union. In 1902 Pamela married Victor Bulwer-Lytton, 2nd Earl of Lytton. Churchill married later, in 1908. Winston and Pamela “remained on affectionate terms” and Winston “continued to write to her for the rest of his life including two sympathetic letters after the deaths of her sons: Anthony, the eldest, in a 1933 air crash and John, at El Alamein in 1942” while Winston was wartime prime minister.

Davina, too, experienced a Second World War loss. Her husband was killed in France in May 1940 less than two weeks after Churchill became wartime prime minister. Churchill’s political right hand and eventual successor, Robert Anthony Eden (1897-1977) had been a close friend of Davina’s husband. Although married, Eden and his wife were increasingly estranged. After the death of Davina’s husband, Eden and Davina found solace in one another and “her presence was to be a constant factor over the next five years.” (Thorpe, The Life and Times of Anthony Eden, First Earl of Avon)

But Eden eventually lost Davina to a Byronic war hero, Christopher Montague “Monty” Woodhouse (1917-2001). Ironically, the two met at Eden’s home, to which Eden invited Monty for a wartime briefing in July 1944. Monty and Davina wed on 28 August 1945. Their marriage lasted half a century, until Davina’s death. During Churchill’s second and final postwar premiership, Monty played a significant role in advocating and precipitating the Iranian coup of 1953 and later served as a Member of Parliament.

PLEASE NOTE THAT A CONSIDERABLY MORE DETAILED DESCRIPTION OF THIS ITEM IS AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST.

Reference: Cohen A240.1(III).a, Woods/ICS A123(aa), Langworth p.258. Item #006512

Price: $12,500.00