By Winston S. Churchill

First published in 1987 by Churchill Literary Foundation, New Hampshire

"...so vivid had my fancy been that I felt too tired to go on. Also my cigar had gone out,

and the ash had fallen among all the paints."

(The Dream, closing lines)

The Dream is Churchill's intriguing essay about a ghostly reunion with his father, Lord Randolph Churchill, in which Winston recounts the world events that have transpired since his father's death - without revealing his own role in them.

The Dream is Churchill's intriguing essay about a ghostly reunion with his father, Lord Randolph Churchill, in which Winston recounts the world events that have transpired since his father's death - without revealing his own role in them.

Where to begin? First there is the story - compelling, insightful, supernatural, psychologically rich, poignant.

Then there is the story of how Churchill was induced to tell the story - itself poignant.

And finally there is the story of how the story waited to be published, which only further fuels fascination and speculation.

Winston Churchill's father, Lord Randolph, died in January 1895 at age 45 following the spectacular collapse of both his health and political career. His son Winston was 20 years old.

A little more than a year later, in a letter to Sir Algernon West, expressing gratitude for a rare positive article about his father authored by West, Churchill would write about his father "... my memories are slender & few" intimating Churchill's admiring but painfully distant relationship with his father.

A few years later, Churchill would seek permission to write his father's biography and then spend two and a half years researching and writing - a major literary effort, but apparently an emotional one as well. Of the work, Churchill wrote to Lord Rosebery on 11 September 1902 "It is all most interesting to me - and melancholy too" (R. Churchill, WSC, Companion Volume II, Part 1, p.438).

Of course history and longevity would dramatically favor the son, but when Randolph died, Winston dwelt very much in his father's shadow, both emotionally and in terms of the political career to which he already aspired. It is in this small, intimate piece of writing that we catch Churchill with that shadow on the eve of his 73rd birthday.

The story goes that in May 1945, a former Master at Harrow - Churchill's alma mater - found and purchased at auction a damaged portrait of Lord Randolph Churchill, which he sent to then Prime Minister Winston Churchill. According to Churchill, a "foggy afternoon in November 1947" found him in his "studio at the cottage down the hill at Chartwell" attempting to paint a copy of the portrait when he turned around to find his father sitting in a red leather armchair, looking just as Churchill "had seen him in his prime." What ensued was a conversation about what had - and had not - changed since Randolph's time, ranging from trivialities and individual personalities to politics and the broad sweep of world affairs. Churchill, of course, never reveals his role in much of this history.

Churchill's summary observations and appraisals to his father make a worthwhile study in themselves. But these are perhaps overshadowed by the emotional overtones which psychologists and sentimentalists will doubtless continue to parse for years to come.

Churchill oscillates between conveying failures and accomplishments to which he was, of course, an undisclosed party. Threading the piece is Randolph's bemusement or disapproval of his son. In the opening he says of Churchill's painting "I am sure you could never earn your living that way." When Churchill speaks of how his father brought him up to regard the democratic process, Randolph exclaims: "I was not going to talk politics with a boy like you ever. Bottom of the school! Never passed any examinations, except into the Cavalry! Wrote me stilted letters."

It is only with this disapproval that Churchill affords himself his father's expression of affection: "But of course you were very young, and I loved you dearly... Fathers always expect their sons to have their virtues without their faults." Only in the final paragraphs, as a "stupefied" Randolph struggles to digest the scope of world events related by his son does Churchill let his father show a hint of approval: "...you seem to know a great deal... I never expected that you would develop so far and so fully... I really wonder you didn't go into politics. You might have done a lot to help." But then the moment vanishes and so does Randolph. Churchill is "too tired to go on" and cannot finish his father's portrait, his cigar has gone out and ash has "fallen among all the paints."

All this is fascinating by itself, but what truly makes the story is how it came to be written and published.

Martin Gilbert relates that in late 1947 during a meal at Chartwell with his son Randolph and daughter Sarah, the latter asked her father "If you had the power to put someone in that chair to join us now, whom would you choose?" Churchill replied "Oh, my father, of course" and told the children of the ghostly incident that had recently taken place in his studio. His children encouraged Churchill to commit the incident to paper, which he did.

His family called it "The Dream." Churchill titled it simply "Private Article." Though he was seldom stinting with his words or their publication, Churchill locked the essay in a box where it remained, willed to his wife.

Churchill died on 24 January 1965 - the same day his father died seventy years before. The Dream was first published a year after Churchill's death, on 30 January 1966, in the Sunday Telegraph and was subsequently included in the The Collected Essays of Sir Winston Churchill (1976).

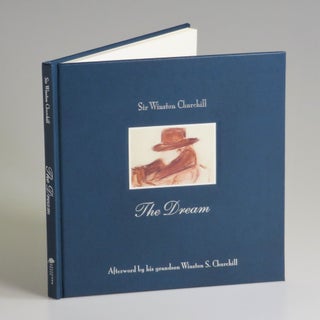

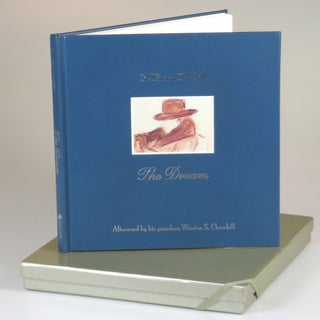

However, The Dream was not published in book form until September 1987, four decades after it was written and more than 22 years after Churchill's death.

Fortunately, the edition rose to the occasion of the long wait. Richard Langworth of the International Churchill Society presided over a lovely limited edition of 500 hand-numbered copies. This was an elaborate production, printed on acid-free archival paper and bound in padded red leather with gilt decoration and the Churchill arms blind stamped on the front cover. All edges are gilt, with head and foot bands, as well as a satin page marker and silk endpapers. Langworth contributed a worthy Foreword and Sal Asaro a color illustration from an oil painting commissioned by the publishers. The first twenty copies were bound with French handmade endpapers and gifted as presentation copies to recipients including HM the Queen and Presidents Reagan and Mitterrand.

Fortunately, the edition rose to the occasion of the long wait. Richard Langworth of the International Churchill Society presided over a lovely limited edition of 500 hand-numbered copies. This was an elaborate production, printed on acid-free archival paper and bound in padded red leather with gilt decoration and the Churchill arms blind stamped on the front cover. All edges are gilt, with head and foot bands, as well as a satin page marker and silk endpapers. Langworth contributed a worthy Foreword and Sal Asaro a color illustration from an oil painting commissioned by the publishers. The first twenty copies were bound with French handmade endpapers and gifted as presentation copies to recipients including HM the Queen and Presidents Reagan and Mitterrand.

A second, less elaborate edition of 1,000 copies published by the International Churchill Society followed in 1994, bound in heavy maroon textured wrappers. Richard Langworth reports that "Seventy copies of this edition, plus ten proof copies, were specially bound in dark green leather boards for the Churchill Family, celebrating the 120th birthday of Sir Winston." These eighty copies feature marbled endpapers, gilt page edges, and an additional four pages about the "Commemorative Edition", and are either numbered 1-70 or labeled "proof copy."

© 2014 Churchill Book Collector. All rights reserved.