A 6 November 1928 telegram from future president Franklin D. Roosevelt to his essential aide, confidante, and de facto chief of staff Marguerite "Missy" LeHand, on the night of the exceptionally close election that made him Governor of New York

New York: 1928. Telegram. This striking piece of ephemera captures a pivotal moment of twentieth century political history and the singular working relationship between the man who would become America’s longest-serving president and the woman who would serve as his de facto chief of staff.

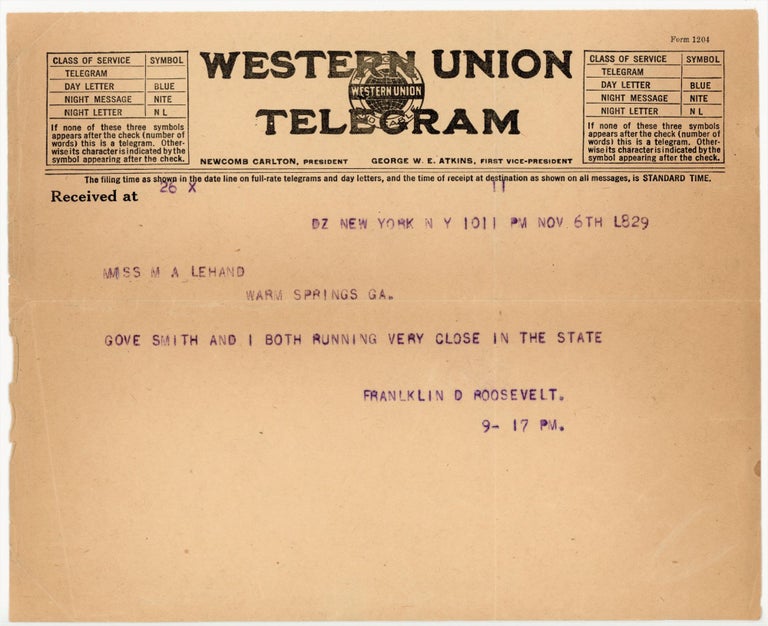

This is a 6 November 1928 telegram from Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882-1945) to Marguerite Alice “Missy” Lehand (1894-1944). Print in six lines reads: “DZ NEW YORK N Y 1011 PM NOV 6TH L829 | MMISS [sic] M A LEHAND | WARM SPRINGS GA. | GOVE SMITH AND I BOTH RUNNING VERY CLOSE IN THE STATE | FRANKLIN D ROOSEVELT. | 9- 17 PM”. The telegram is printed on 8 x 6.5 inch (20.3 x 16.5 cm) “WESTERN UNION TELEGRAM” stationery. The dark purple type remains distinct, if slightly variable in ink. The paper is inevitably toned but nearly complete, with fractional closed tears along the left edge, a tiny stain along the lower right edge, a single horizontal crease, and a single vertical crease. The telegram is protected within a clear, removable, archival sleeve.

On the night of 6 November 1928, when FDR sent this telegram, the providential arc that made him America’s longest-serving president teetered on an electoral edge.

In 1921, FDR’s promising political career was abruptly derailed by an illness that resulted in lifelong paralysis of his legs. When New York Governor Al Smith became the Democratic Party’s presidential nominee in June 1928, Democrats had to choose a new candidate for governor of New York. It was not FDR. Death, ill health, and failure to attract broad support sidelined various candidates. A month before the November 1928 election the Democrats still lacked a candidate – and that candidate was critical, since Smith needed a strong gubernatorial contender to help him win the state’s electoral votes in the presidential race. Recruited by Smith, a hesitant FDR agreed to run only just before he was formally nominated.

FDR and his campaign team spent the evening of 6 November at their Biltmore Hotel campaign headquarters. Lehand, convalescing from an illness, was at FDR’s retreat in Warm Springs, Georgia. Contrary to this upbeat telegram, Smith was already losing and Roosevelt went home at about midnight without optimism. Only at about 4:00 AM on 7 December did it become clear FDR had won – albeit with less than 50% of the votes cast and little over half a percent more than his opponent. Four eventful years later, domestic economic crisis brought Roosevelt to the White House.

Lehand had already been with FDR for nearly a decade when she received this telegram. “Missy” (so-called because one of the Roosevelt children had trouble pronouncing “Miss”) was engaged by FDR at Eleanor Roosevelt’s suggestion, initially handling his 1920 campaign schedule. Thereafter she spent all but her final, impaired years as his essential aide and confidante, calling him “EffDee”. A statistic speaks to how swiftly Lehand became essential to FDR. “From 1925 to 1928, Roosevelt spent 116 of 208 weeks away from home, trying to regain full use of his limbs. Eleanor was with him for four of those weeks… Missy LeHand for 110.” (Black, Roosevelt, p.158)

FDR’s as-yet unwarranted optimism in this telegram to Lehand makes sense in context. The illness that kept her in Warm Springs has been described by some as a nervous breakdown, attributed by some to her concern that FDR’s run for governor would interrupt his physical therapy and impede his recovery.

Though officially titled “Personal Secretary”, LeHand was arguably the most influential figure during FDR’s long presidency and, as many have asserted, his de facto Chief of Staff. She had her own bedroom in the executive mansion in Albany and in the White House, serving FDR until she was incapacitated by a stroke in June 1941. When she died in July 1944 – allegedly from further strokes precipitated by seeing FDR’s haggard appearance in a cinema newsreel – FDR publicly praised her for “devoted service” and being “utterly selfless in her devotion to duty.”. Item #006716

Price: $1,600.00